Reference and Value Types in Swift

In this post we are going to examine the differences between reference and value types. We’ll introduce both concepts, take a look at their strengths and weaknesses, and examine how we can take advantage of them in Swift.

Reference Types

Reference type: a type that once initialized, when assigned to a variable or constant, or when passed to a function, returns a reference to the same existing instance.

A typical example of a reference type is an object. Once instantiated, when we either assign it or pass it as a value, we are actually assigning or passing around the reference to the original instance (i.e. its location in memory). Reference types assignment is said to have shallow copy semantics.

In Swift, objects are defined using the class keyword:

class PersonClass {

var name: String

init(name: String) {

self.name = name

}

}

var person = PersonClass(name: "John Doe")

Value Types

Value type: a type that creates a new instance (copy) when assigned to a variable or constant, or when passed to a function.

A typical example of a value type is a primitive type. Common primitive types, that are also values types, are: Int, Double, String, Array, Dictionary, Set. Once instantiated, when we either assign it or pass it as a value, we are actually getting a copy of the original instance.

The most common value types in Swift are structs, enums and tuples can be value types. Value types assignment is said to have deep copy semantics.

Copy Semantics

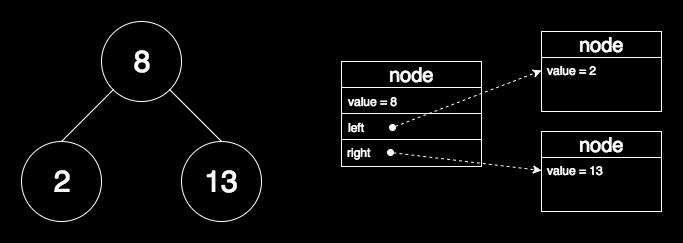

I am going to illustrate the difference between copy semantics through a practical example. Suppose we are working with a generic tree data structure:

class Node<T: Comparable> {

let value: T

var left: Node?

var right: Node?

convenience init(value: T) { […] }

init(value: T, left: Node?, right: Node?){ […] }

func add(value: T) { […] }

}

We can easily create an instance of a binary tree as follows:

let binaryTree = Node(value: 8)

tree.add(2)

tree.add(13)

Now, let’s take a look at the different behaviors of copy semantics.

Shallow copy (reference types)

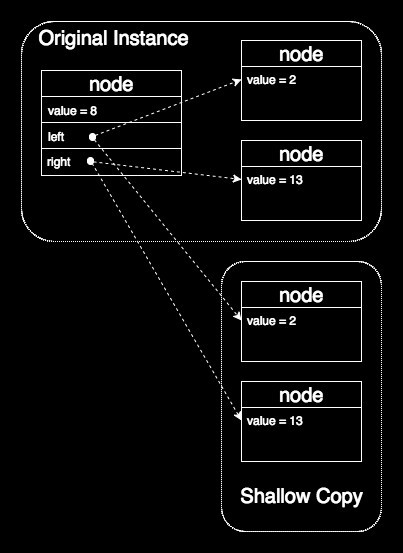

When copying reference types, the Swift compiler copies the reference of the instance. But not its properties. Hence, when creating multiple copies of a reference type object each copy will share the same data, represented by the instance properties.

Deep copy (value types)

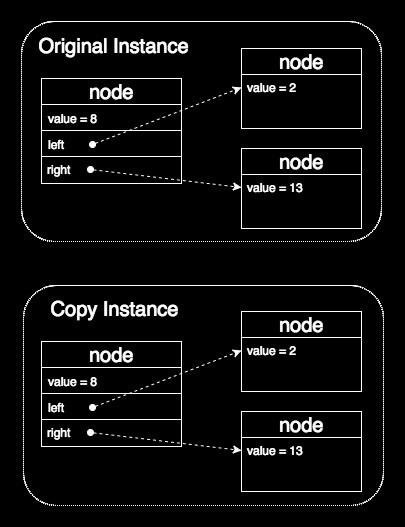

When copying value types, the Swift compiler makes a brand new copy of the original instance. This means all original instance properties are copied into a new one. This process is replicated for each property which is a value type itself. Hence, when creating multiple copies of a value type object each copy will be a new separate instance with no shared data.

The Issue With Reference Type Instances: Implicit Data Sharing

In order to show a typical issue with reference types, let’s define a class to represent a point in a 2D space.

class PointClass {

var x: Int = 0

var y: Int = 0

init(x: Int, y: Int) {

self.x = x

self.y = y

}

}

Now, what happens if we instantiate a PointClass object and assign it to another one?

var pointA = PointClass(x: 1, y: 3)

var pointB = pointA

Because PointClass is a reference type, the last statement is actually assigning the reference to pointA to pointB. We can graphically represent the above scenario as follows:

In this situation, pointB and pointA share the same instance. Hence, any change to pointA will reflect on pointB and vice versa. This may be fine in many circumstances, but is also a very common source of subtle bugs.

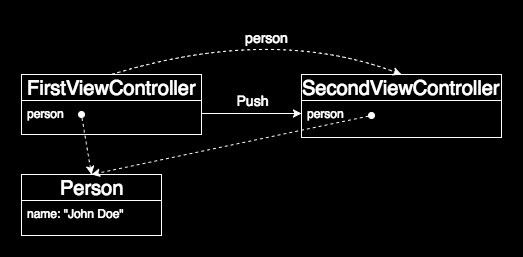

Let’s take a look at a very easy way of running into the implicit shared data issue. Suppose we instantiated a view controller and assigned it a reference to a Person object (our object model) instance. Then, responding to the user interaction, we push another view controller (on top of the first one) and assign it the same reference instance. We can visualize this particular scenario as follows:

Since both view controllers have been assigned the same reference instance, if we modify any of its properties inside SecondViewController we end up modifying the original (shared) Person instance initially assigned to FirstViewController. Hence, any modifications to the object model made inside SecondViewController will be propagated to FirstViewController.

Going back to our original example, one way to avoid the implicit data sharing issue would be to explicitly create a copy of the instance. Instead of just assigning pointA, we could manually create a copy and assign it:

var pointB = pointA.copy()

Now, pointB would have its own separate reference and there will be no more shared data between pointA and pointB. This technique works fine but has a few disadvantages:

- Having to either:

- Inherit from

NSObjectand implementNSCopying. - Implement a new Copyable protocol for copying objects in Swift.

- Inherit from

-

Explicitly calling

copy()for each assignment introduces some overhead. - It is easy to forget to call

copy()for each assignment.

Value Type Instances: No Implicit Sharing

When assigning value types, the compiler will automatically create (and return) a copy of the instance. Let’s see what happens if, instead of defining our 2D point as a class (reference type), we make it a struct (value type).

struct PointStruct {

var x: Int = 0

var y: Int = 0

init(x: Int, y: Int) {

self.x = x

self.y = y

}

}

Now, we can create an instance of PointStruct and assign it to another one.

var pointA = PointStruct(x: 1, y: 3)

var pointB = pointA

Because PointStruct is a value type, the last statement is creating a copy of pointA to be assigned to pointB. This makes the assignment safe as the two instances are distinct. We can graphically represent this situation as follows:

We can see that pointB has its own separate reference and there will be no shared data between pointA and pointB. This shows that by using value types we can easily make sure that all our instances are distinct and don’t share any data.

From a performance standpoint, using value types doesn’t add a significant overhead:

- Copies Are Cheap

- Copying a primitive type (

Int,Double, …) takes constant time. - Copying a struct, enum or tuple of value types takes constant time.

- Copying a primitive type (

- Extensible data structures use copy-on-write

- Copying involves a fixed number of reference-counting operations.

- This technique is used by many standard library types:

String,Array,Set,Dictionary, ….

In addition to the above, another performance benefit of value types is that they are stack allocated, which is more efficient than heap allocation (used for reference types). This makes access faster but comes with the drawback of having to drop support for inheritance.

It is important to point out that structs, enums and tuples are true value types only if all their properties are value types. If any of their properties are a reference type, we still could run into the implicit data sharing issues illustrated in the previous paragraph.

Let’s take a look at the following struct:

struct PersonView {

let person: PersonStruct

let view: UIView

}

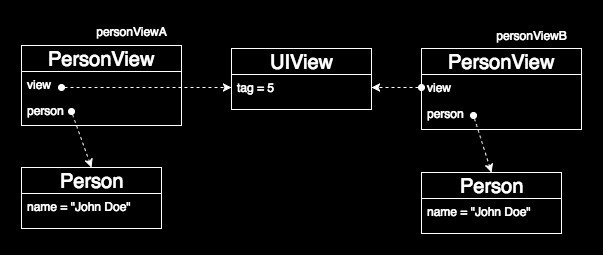

Our intended goal would be to create a container to keep track of a person and handle a view showing all related info. We may feel confident that the above code is sound; after all we declared all properties using let, right? Well, unfortunately, that is not the case. Because the view property is a reference, as UIView is a reference type, we are still able to change its properties! But there is an even more subtle source of bugs. In order to illustrate that, let’s create an instance of PersonView and make a copy:

let personViewA =

PersonView(person: PersonStruct(name: "John Doe"),

view: UIView())

let personViewB = personViewA

Now, because view is a reference type, what happens is that both instances of PersonView are sharing the same property! This entails that, if we modify the view property of any of the instances, we end up actually modifying the shared view. The following diagram should make easier to see this and help us recognize that, once again, we ran into the implicit data sharing issue we discussed earlier:

Reference Types, Value Types and Immutability

Immutability: the property of an instance whose state cannot be modified after it is created.

Immutability is a very important property and it is strictly related to the functional programming paradigm. We saw that by using value types we are able to create instances that preserve their state indefinitely, which are immutable by definition. Immutable objects have some interesting pros and cons.

Pros:

- Immutable objects share no data and, therefore, have no shared state among instances. This avoid the issue of unexpected changes caused by side effects.

- A direct consequence of the previous point is that immutable objects are inherently thread-safe. This means we don’t need to worry about race conditions and thread synchronization.

- Because immutable objects preserve their state, it is easier to reason about your code.

Cons:

- Immutability doesn’t always map efficiently to machine model. A typical example of this are algorithms that perform in-place modifications (like Quicksort). Those are not easy to implement using value types while, at the same time, maintaining the original performances.

In Swift, we can define variables using two different keywords:

var: defines mutable instances.let: defines immutable instances.

The above keywords have different behaviors, depending on whether they are used for reference or value types.

Mutable Instances: var

Reference types

The reference can be changed (mutable): you can mutate the instance itself and also change the instance reference.

Value types

The instance can be changed (mutable): you can change the properties of the instance.

Immutable Instances: let

Reference types

The reference remains constant (immutable): you can’t change the instance reference, but you can mutate the instance itself.

Value types

The instance remains constant (immutable): you can’t change the properties of the instance, regardless whether a property is declared with let or var.

Which Type Should You Choose?

A very common question is: “How can I decide when to use reference types and when to use value types?”. You can find a lot of discussions about that over the Internet. Some of my favorite examples are:

- Should I use a Swift struct or a class?

- Friday Q&A 2015–07–17: When to Use Swift Structs and Classes

- A Warm Welcome to Structs and Value Types

- RE: Should I use a Swift struct or a class?

- Structs vs Classes

- Reference vs Value Types in Swift

As a basic rule, we are forced to create reference types every time we are subclassing from NSObject. This is a common scenario when interacting with the Cocoa SDK. There are some common rules, provided by Apple, for using reference types versus value types. I have summarized them below.

Reference Type When:

- Subclasses of

NSObjectmust be class types. - Comparing instance identity with

===makes sense. - You want to create shared, mutable state

Value Type When:

- Comparing instance data with

==makes sense (Equatableprotocol). - You want copies to have independent state.

- The data will be used in code across multiple threads (avoid explicit synchronization).

Interestingly enough, the Swift standard library heavily favors value types:

- Primitive types (

Int,Double,String, …) are value types. - Standard collections (

Array,Dictionary,Set, …) are value types.

By taking a look at the Swift Standard Library reference it is possible to gather the exact numbers to confirm the above statement. Here is the split up of types:

- Classes = 4

- Structs = 103

- Enums = 9

Aside from what is illustrated above, the choice really depends on what you are trying to implement. As a rule of thumb, if there is no specific constraint that forces you to opt for a reference type, or you are not sure which option is best for your specific use case, you could start by implementing your data structure using a value type. If needed, you should be able to convert it to a reference type later with relatively little effort.

Conclusion

You can download a playground with the code from this post here.

In this post we examined the differences between reference and value types. After looking into a common issue with implicit data sharing, we saw how it is possible to avoid that by using value types instead of reference types.

We also introduced the concept of immutability and saw how it applies to reference and value types in Swift. Lastly, we reviewed some use cases for which the choice between reference and value types is quite straightforward. For all other cases, experimentation is the best way to find out which could be the best option.