Protocol Oriented Programming in Swift

In this post we are going to take a look at some common issues with application design. We’ll delve into the limitations of classical Object-Oriented Programming and how we can address those using a different approach. In particular, we’ll examine which patterns are currently available in Swift to follow such an approach.

Object-Oriented Programming 101: Classical Inheritance

For a few decades now, Inheritance has been the most commonly used technique to represent the entities we interact with in the context of our application. If well used, this technique is quite useful. But, in many cases, Inheritance has some major limitations in representing the complexity required by the relationships among application entities.

A hierarchy example

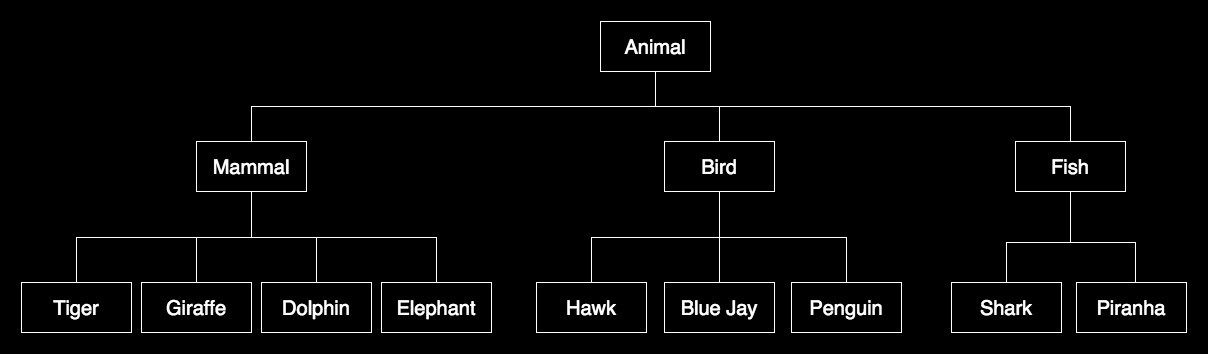

Let’s start with a fictional example of an already existing application whose main entities can be illustrated in the following class diagram:

Now, suppose we are tasked to update our application to incorporate some new business requirements. The example above is just a very simple hierarchy. But we’ll find out that, as we try to add more functionality, it is very easy to end up with a working solution that makes the whole architecture more fragile and less efficient.

Adding new functionality

Our new business requirement is to introduce a further categorization of our animals, based on how they move around in their environment: running, swimming or flying. Each of these categories will provide some new specific functionality. As a first experiment, we will try to perform this task by relying on Classical Inheritance only.

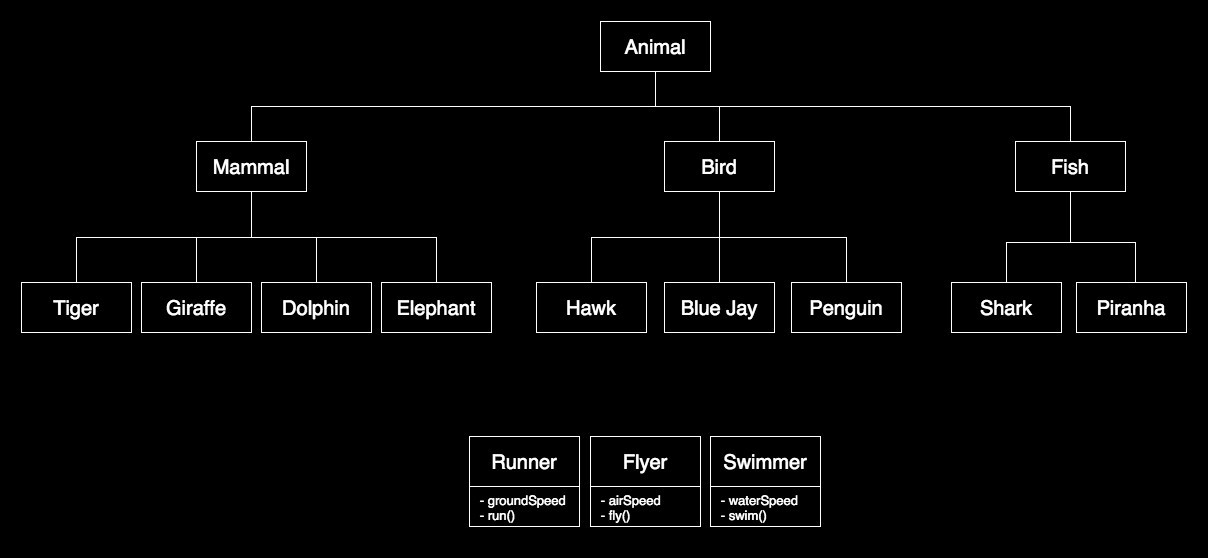

The most straightforward way to add the required new functionality, using the Inheritance pattern, is to further classify our zoo animals as Runner, Swimmer and Flyer. Each one of these classes will have to implement a specific method and property.

Unfortunately, in the above scenario, our existing animals don’t fit very well in this new additional classification. Some of them belong to more than one of the new classes. A significant example of how the new functionality doesn’t fit well is represented by the Penguin. Even if it is a Bird, it can’t fly, as would be the common expectation. Instead, it can run (well … sorta) and swim. Therefore, the Penguin is not a Flyer but both a Runner and Swimmer. This counterexample to the notion that all birds can fly means that it is not possible to implement Flyer’s fly() method inside the Bird class.

A possible solution would be to duplicate the required code for each new subclass. This looks easy enough, but then we’d have to potentially deal with a lot of code duplication. In order to avoid that, we are instead going to push the new functionality up in the hierarchy, assigning it to the closest common ancestor. We are basically trading-off code duplication for added complexity.

As we just saw, we started from a very simple problem and, by relying solely on Inheritance, ended up designing a taxonomy of tightly related classes built up on top each other. This may work fine with the specific current implementation, but it lacks flexibility and it could be very hard, if not impossible, to make substantial changes to the application architecture in the future.

The issues with Classical Inheritance

… the problem with object-oriented languages is they’ve got all this implicit environment that they carry around with them. You wanted a banana but what you got was a gorilla holding the banana and the entire jungle.

Joe Armstrong

The following is my personal point of view on the main issues of Classical Inheritance:

-

Limited relationship representation: If we just rely on Classical Inheritance, the only kind of relationship we can represent is an “is-a” (which defines a class that inherits from its parent). This limits the way we can design our application entities. For instance, being able to use “has-a” relationships would allow us to represent an object as containing simpler objects. With this extra degree of flexibility, it would be possible to decompose functionality across multiple cooperating objects.

-

Insufficient flexibility: When working with Inheritance hierarchies, during the initial design phase, we are required to come up with an initial taxonomy of objects describing your application. Unfortunately, it is almost impossible to predict how the requirements will evolve and, sooner or later, we will find out that what we designed in the beginning can’t be further adapted to include a specific use case. This is a direct consequence of the limited relationship representation issue.

-

Fragile base class: In the context of an Inheritance hierarchy, the superclass is said to be fragile. This is because an Inheritance hierarchy is made of tightly coupled classes, and any change to its superclass will affect all the related subclasses in a ripple effect. It is easy to find out that even a slight modification to the superclass can potentially have disastrous consequences and negatively affect the entire hierarchy. In addition to this, even if we are careful enough to make sure our changes have no unintended side effects, it is really easy to implement a superclass that has too many responsibilities. This break the “Single responsibility principle” and adds to the fragility of our architecture.

-

Multiple Inheritance: In an effort to make Inheritance more flexible, some programming languages introduced the concept of Multiple Inheritance. The main idea is to allow a subclass to inherit from more than one parent. Unfortunately, this pattern comes with added complexity and ambiguities (such as the “Diamond Problem”) that greatly limits its adoption. In fact, many modern programming languages don’t support Multiple Inheritance by choice (Swift is one of them).

A better approach to modeling: Composition over Inheritance

“Program to an interface, not an implementation.”

“Favor ‘object composition’ over ‘class inheritance’.”

A more efficient code reuse can be achieved by adopting Composition instead of Inheritance. Through Object Composition we are able to combine simple objects into more complex ones.

Interfaces, Traits and Mixins

The original idea of Composition leverages the concept of Interface, in which we declare a list of methods that need to be implemented by each class that wants to support the new functionality. Over time, different languages introduced further evolutions of this concept, namely Trait and Mixin. Different languages may define Interfaces, Traits and Mixins in a different way, or may have overlapping definitions. But, generally speaking, such abstractions can be briefly summarized as follows:

-

Interface: contains method declarations.

-

Trait: an Interface containing method bodies.

-

Mixin: a Trait with its own properties (state).

An improved application architecture

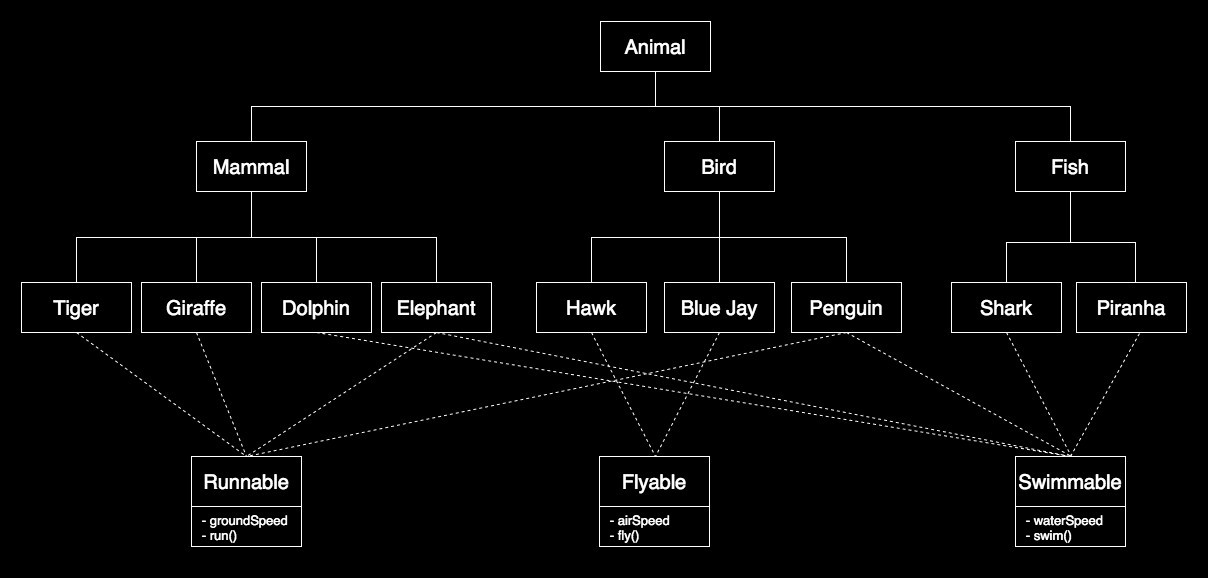

We will now look into how it is possible to overcome the intrinsic limitations of Classical Inheritance by introducing Object Composition in the design of our application architecture. Initially, we tried to introduce a few new classes: Runner, Swimmer and Flyer. Now, as we are moving away from Inheritance, we will, instead, create corresponding interfaces that allow us to declare the new functionality we need. As a consequence of this decision, the former Runner, Swimmer and Flyer classes will become, respectively, the Runnable, Swimmable and Flyable interfaces. These interfaces are going to declare the functionality that can be composed with existing classes to extend them with new capabilities.

Now, our zoo animals can be implemented by composing a concrete class with one or more interfaces. The resulting improved architecture is illustrated in the following diagram:

The Swift way: Protocols and Protocol Extensions

Swift adopted its own terminology to define the constructs illustrated in the previous paragraph:

-

Protocols: provide a way of creating interfaces.

-

Protocol Extensions: allow to implement traits.

-

Conforming to a protocol: implementing a specific interface (i.e.: protocol).

Even if it is possible to add properties to a Protocol, the Swift compiler will still require us to initialize each property in any class that conforms to the protocol where they are declared. It is important to notice that the property values are stored in the conforming concrete class, and not in the Protocol itself. That is the reason why we are usually told that Swift doesn’t fully support mixins.

Going back to our application, let’s take a look at how we can implement our composable architecture in Swift. For instance, the functionality for the Runnable entity can be described as follows:

protocol Runnable {

var groundSpeed: Double { get }

func run() -> String

}

extension Runnable {

func run() -> String {

return "Running at \(groundSpeed) mph"

}

}

The Runnable Protocol defines the Interface, while the Runnable Protocol Extension provides a default implementation (Trait) of the interface methods. Classes that conform to the Runnable Protocol, by implementing its interface, could either take advantage of the default implementation (provided by the Protocol Extension), or override it to provide their own customization.

The same approach can be used to implement the functionality for Swimmable and Flyable:

protocol Swimmable {

var waterSpeed: Double { get }

func swim() -> String

}

extension Swimmable {

func swim() -> String {

return "Swimming at \(waterSpeed) mph"

}

}

protocol Flyable {

var airSpeed: Double { get }

func fly() -> String

}

extension Flyable {

func fly() -> String {

return "Flying at \(airSpeed) mph"

}

}

Now, in order to represent that penguins can both run and swim, we can easily implement the Penguin class by conforming to both the Runnable and Swimmable protocols:

class Penguin : Bird, Runnable, Swimmable {

var groundSpeed = 2.0

var waterSpeed = 25.0

}

Conclusion

You can download the complete code sample here.

In this article we examined the most common issues with Classical Inheritance and investigated how we can address them. We achieved our goal by designing a more flexible architecture through the adoption of Object Composition, in order to move away from tightly coupled hierarchies.

In particular, we explored how to implement such an improved architecture by exploiting Swift’s Protocols and Protocol Extensions. We learned that we can create our Protocols and extend them using Protocol Extensions to provide default method implementations. This allows us to create much cleaner code, compared to what we could implement by relying solely on the Classical Inheritance pattern.